Please, Touch the Artwork 2 by Thomas Waterzooi

on love letters

You are longing to meet again, dear Louise. So am I. I am yearning to embrace you and to hold you in my arms. By the end of next week, or thereabouts, I hope to be able to tell you exactly when we shall be able to see each other.

So writes Gustave Flaubert to the poet Louise Colet in a love letter dated 15-16 May, 1852. Love letters existed long before Flaubert’s, in the Indian Bhagavata Purana and Ancient Egypt, in Imperial China and Ancient Rome, the Middle Ages and throughout the Victorian era. Love letters were exchanged between such individuals as Flaubert and Colet, Gilbert Bradley and Gordon Boushar, Rachel Carson and Dorothy Freeman, Virginia Woolf and Vita Sackville-West, and even Emperor Marcus Aurelius and Marcus Cornelius Fronto among many others.

Love letters did not exclusively contain proclamations of love but also the author’s current fixations, opinions, and commentary on current events.

This week I’ve been reading Rodogune and Théodore. How utterly disgusting are Voltaire’s commentaries on Corneille! What stupidity! And yet he was a man of wit. But wit is of little use in the arts. To inhibit enthusiasm and to discredit genius, that is about all.

Love letters persist to today, though have been adapted into text messages, snapchats, and other methods of communication brought on by the internet. James Joyce would have easily adapted to the modern age of sexting with his wife Nora. One form the term has been employed to describe, erroneously, are video games.

- Child Of Light Is A Love Letter To Fables And JRPGs - Kotaku

- This love letter to classic JRPGs takes an hour to get going… - PC Gamer

- Blasphemous Preview: A Blood-Soaked Love Letter to Castlevania - IGN

- South Of Midnight Review - A Love Letter To The American Deep South - GameSpot

- Sea of Stars: A Love Letter to RPGs Old | Welcome to the Game Room

- Dune: Awakening review: "...still a true Dune love letter" - GamesRadar

- RagnarRox Explores World of Horror, "A Lovecraftian Love Letter to Junji Ito" - Stride PR

- Tormenture Is A Love Letter To Retro Games… - TheGamer

- Astro Bot: A Love Letter To Video Games, PlayStation & You - Gamer Social Club

- With 'Wu-Tang: Rise of the Deceiver,' Hip-Hop Gets a Love Letter… - Rolling Stone

- Split Fiction Review (PS5) – A Love Letter To Video Gaming - Finger Guns

The term love letter is usually deployed where homage would be more fitting. The main feature these games lack that love letters contain is being directly addressed to an individual and containing explicit adulation towards that individual. Most of the games are not directly addressing the subject they are described as loving. Instead they merely adopt a form, a mechanic, a style from that source and name it as an inspiration in interviews or press releases.

In regards to Child of Light, “The developers have called it a love letter to JRPGs.” This is apparently supported by, “fights have a continually running meter that is reminiscent of a favorite JRPG of mine, Grandia,” “the ability to swap between members at any time, as in Final Fantasy X.” Peter Tieryas adds fables to the subject of the love letter, the evidence being: “hand-painted environments and character portraits make the game feel like you’re living in an illustrated children’s fantasy book.” Eiyuden Chronicle: Hundred Heroes is, “a love letter to classic JRPGs,” because of slow pacing, linear progression, turn-based combat, diverse party of characters, varied music tracks, combat mechanics, character animations, and animals. Blasphemous is a love letter to Castlevania because of “jumping, sliding, and non-linear exploration.” South of Midnight is a love letter to the American Deep South because it reads as authentic and well researched in the fashion, colors, sights, and sounds of that place and its people. Sea of Stars is a love letter to Chrono Trigger and other “classic JRPGs” because it has an NPC reciting the same dialogue from that SNES game as well as, “turn-based combat, a wide range of areas to explore and, of course, an overworld.” Dune Awakening is a “love letter to the Dune series” because it recreates “Iconic moments, from painful encounters with Bene Gesserit truthsayers to cruising above the desert in wildly flapping ornithopters.” World of Horror is a love letter to Junji Ito because it is the primary inspiration behind the game. Tormenture is a love letter to retro games because it recreates the visuals of 1980’s PC games and the era's vibes. Astro Bot is a “love letter to video games, PlayStation & you” because you can find robots dressed up like recognizable characters. Wu-Tang: Rise of the Deceiver is a love letter to hip-hop culture because it features music artists both well known and obscure1. Split Fiction is a love letter to video gaming because it is, “Bold, inventive, and endlessly entertaining.”

Are these features being implemented as a love letter or just taking what was done before and doing it again in a different mixture? Are specific art styles chosen as love letters to their originators or simply because they can make said game stand out amongst the countless games being released? This is why I do not believe these to be even merely implicit love letters. How many games are created because the developer played and enjoyed a game in their adolescence and simply wanted to make another one of those? Wouldn’t most of these games be better described as homages than a love letter? Few of them explicitly address the subject of their love, and most are called love letters simply because the developer listed an older work as a source of inspiration. I would not describe Sable as a love letter to Moebius as it only uses his art style copiously because it is pleasing to look at. There is no acknowledgement or message being directed at the artist. Some of these games require additional legwork outside of itself in order to even determine what they are a love letter to.

We have a problem with how to describe videogames. The fallback most often is to simply name-drop other games it is like. “It’s like Skyrim and New Vegas,” “It’s like Minecraft and PUGB,” “it's like Hades but with cards,” “It’s like Hollow Knight and Dark Souls.” Similarly we have a problem with determining whether a game is a ripoff or simply another iteration in an established genre. Think of Doom-clones and their evolution into simply being first person shooters. The most recent example of this is “Souls-like.” Are games that riff on Dark Souls’ mechanics, tone, and fiction delivery method clones or love letters or an entry into the latest genre that we cannot agree upon a better name for (also looking at “Metroidvania”)? At some point a mechanic or style becomes so widespread that using it can no longer be justifiably described as copying or ripping off the original. We no longer talk about Wolfenstein 3D or Doom when discussing the latest Call of Duty. We no longer call first person dungeon crawling an Ultima-like. Battle royales are no longer copycats of PUBG. It is our own lack of vocabulary that we consistently fall back on lesser descriptors such as Souls-like which relies heavily on insider knowledge as opposed to terms such as dungeon crawler or first person shooter. Some genres are themselves so vast in their progeny that calling something an RPG is not particularly specific or helpful nowadays.

All of this is a prelude to attempting to answer the question, is Please, Touch The Artwork 2 a love letter to James Ensor?

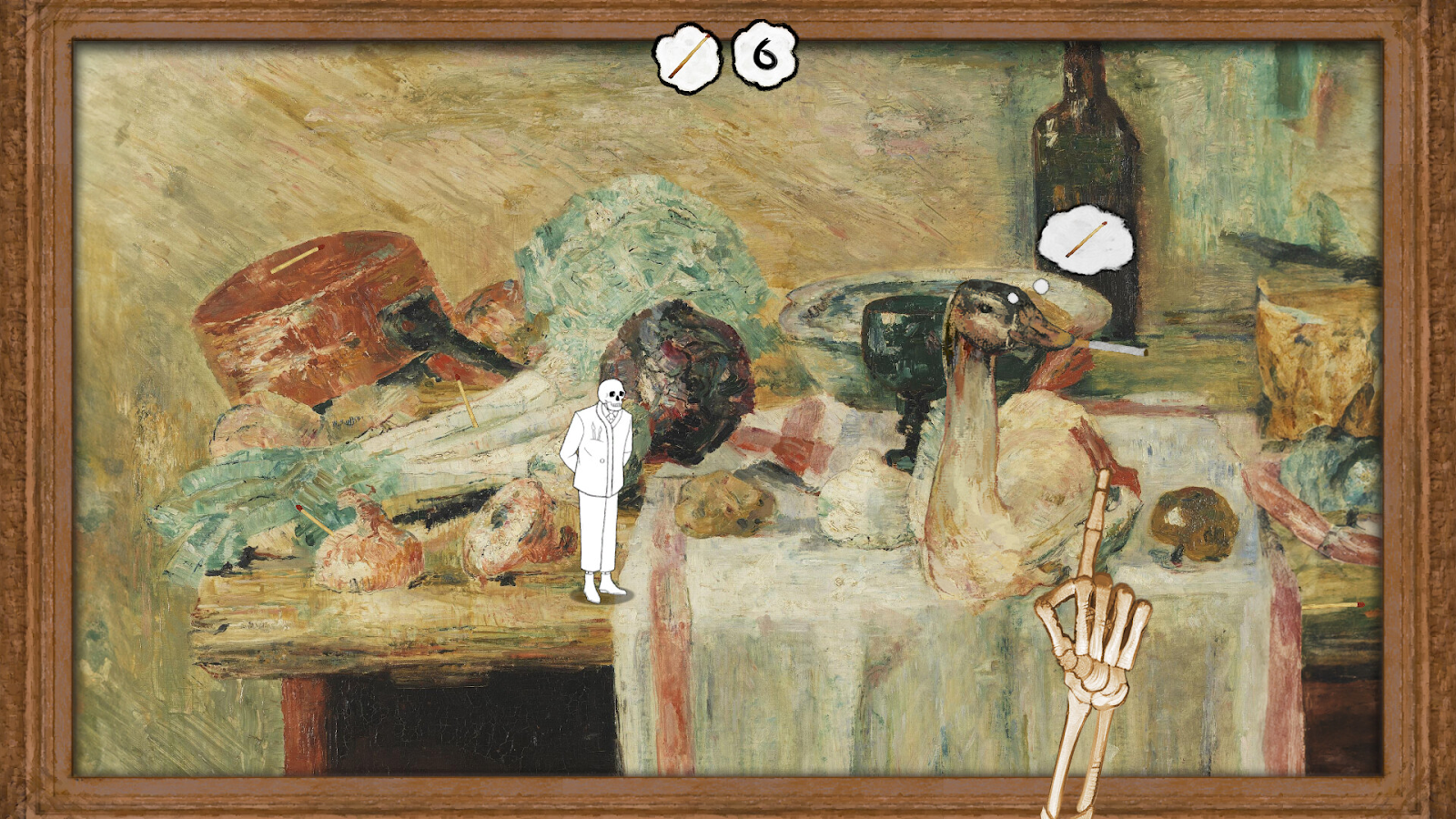

Framed as a museum visit, the player is tasked with tapping points within various works of art, all by James Ensor, in order to solve puzzles and progress forward. Most puzzles require you to examine each painting in detail to find a variety of items hidden within them. This mechanic of seek-and-find wonderfully focuses your attention on the details of the art. It forces you to pay attention to the brush strokes, coloring, and composition of each painting you come across unlike a freeform wandering within an actual museum. This heavy handed method doesn't become something to fight against since the tone is very playful and the solutions never complex.

Each exhibit of paintings follows a collective theme. A beach of hapless laborers and drunks, a bustling city and the interior lives of its residents, still life images of flowers and delectable dishes of fruit and seafood, a festive wedding celebration, and the finale of reaching Ensor’s studio. Throughout all of these you’ll chase the central figure from The Intrigue who slashes at canvases requiring patchwork to restore them. The skeleton figure you have been guiding along is revealed through a crash zoom montage of self-portraits to be Ensor himself, winking at the player before the credits roll.

The painting’s images do not sit still. Most feature crudely animated figures mucking about, drinking, dancing, fighting, chasing, reading, and even a smoking duck (not as in cooked). The crudeness of their animation is due to minimal moving parts, and the parts that do move rotate upon fixed angles. It all accentuates the playful tone, even if one such subject is a woman who promptly dies.

James Ensor was a Belgian artist who lived from 1860-1949. Remembered as an eccentric loner and at the forefront of both Expressionism and Surrealism. The game was created in conjunction with a celebration of the 75th anniversary of Ensor’s death.

‘Ensor tends to be remembered as a one-off figure,’ says Stefan Huygebaert, a curator at Mu.ZEE art museum in Ostend. ‘For many people, he amounts to paintings of masked figures and skeletons. However, by the end of this year, hopefully people will understand there was more to him than that.’ [Christies]

The main problem I have, in regards to answering the question as the game itself is quite lovely, is that the game lacks an explicit addressee within itself. The finale shows a lot of affection towards the artist, and clearly seems to be begging the player to find out who this person is and how to learn more about them. The steam page's short description makes no mention of Ensor. It is not until the “About this game” section that you happen upon Ensor's name. The beginning of the game has the skeleton emerging from the grave of a “Baron James Ensor” with the r a bit obscured in a small detail forgotten about by the ending “reveal.” Even if it may not be direct, as in Thomas opening with a dedication, its focus, content, and credits make it a clear love letter to the artist. I think it certainly reaches closer to that term than a game featuring turn based combat, an over world, and a diverse party of characters being described as a love letter to the JRPGs of your childhood.

Once I have told you that I am working and that I love you, I have said it all. Farewell then, dear beloved Louise, I embrace you tenderly.

Yours. G.

Of these examples listed I think the Wu-Tang one might have the best chance of fulfilling the claim, mainly due to the origin of the game coming from Wu-Tang itself and its focus on being a way of featuring lesser known acts into its soundtrack. Lots of my music taste has come from songs featured in game soundtracks so I do believe in its power to be a tastemaker. ↩